Do you feel like a fraud? Do you think people are being nice if they praise your work or that you’ve been lucky to get this far in business? It’s not you, it’s imposter syndrome – and you’re not alone.

We offer practical tips and advice for you to tackle your own sense of imposter syndrome – and for the manager or organisation to make a difference.

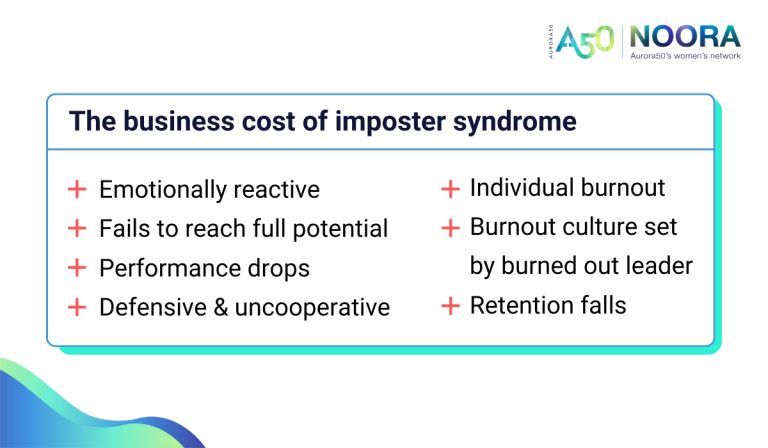

Because there’s a real business cost to imposter syndrome, right down to the corporate culture…

Imposter syndrome describes that feeling of being a fraud, unworthy of your success.

Sufferers of imposter syndrome think they’re going to be ‘found out’, that they are not really competent, and that they are not entitled to their accomplishments.

The syndrome is not related to whether someone has achieved success or not: those affected are simply unable to accept the evidence of their own success.

Those suffering with the syndrome tend to believe compliments and praise are people ‘being nice’ or that luck had been at play more than talent.

Research shows 70 percent of people are affected by imposter syndrome at some point.

Imposter syndrome is more often seen in successful people. Some 25 to 30 percent of high achievers may suffer imposter syndrome.

It is linked to perfectionism and anxiety, and high achievers tend to be affected more.

There can be many causes for the phenomenon to appear more in some people than others.

Family dynamics play a big role, and how a person has been raised will contribute to this. Expectations in childhood can stay with a person for a long time.

Cultural expectations also affect these definitions of success in addition to individual personality traits – most commonly perfectionism.

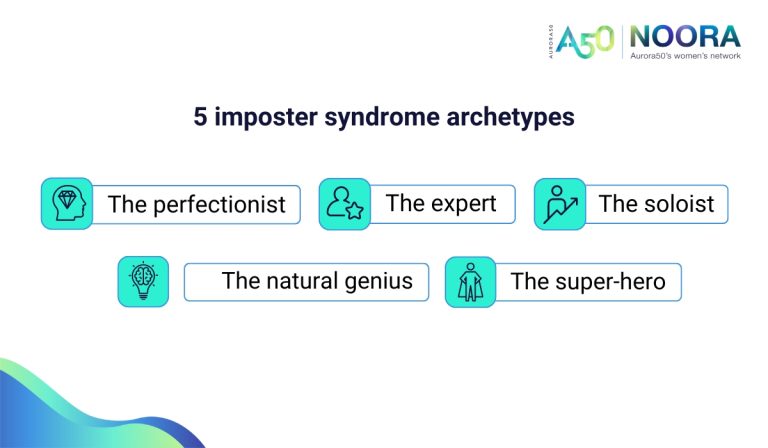

Common traits include:

Externally, these traits can manifest as:

Imposter syndrome can have a significant impact on various aspects of a person’s life, from mental health to overall wellbeing:

A 2022 KPMG study found that 75 percent of women executives have experienced imposter syndrome.

In our experience of training and coaching women in management and on boards, executive women are very likely to struggle.

The term ‘imposter syndrome’ itself was coined by Pauline Clance and Suzanne Imes in the Seventies in a study of high-achieving women.

Sufferers tend to keep it a secret – you are not alone!

Even Michelle Obama has confessed to feeling like an imposter.

Particularly in this region, ‘presenting positive’ can be an issue for women.

They smile and do not admit to any struggles.

In many of our management workshops on imposter syndrome, even when we describe imposter syndrome, women say they don’t recognise it.

But we generally find they identify with the different imposter ‘types’ – especially the super-hero, who feels they have to be a super mum, a super exec, a super sister and a super daughter.

Never feel alone again – join NOORA, the network for corporate GCC business women who lead with impact and share their successes to rise together. Organisations can buy corporate packages and individuals can self-fund their membership.

Plenty of well-known people confess they suffer a touch of imposter syndrome…

Unchecked, imposter syndrome can lead to burnout. Executives set the cultural tone in a company, and are role models to their teams. An exec who is pushing themselves towards burnout unintentionally creates a burnout culture. The cost of burnout then multiplies through their team.

A long-term effect of imposter syndrome and an activated nervous system is exhaustion – that constant feeling like you’re swimming upstream, working extra hard and longer hours to deliver well.

Stressed people are also more emotionally reactive, due to changes in blood flow in the brain. This means they may get defensive, short-tempered, blame others, withdraw or become more suspicious and less cooperative.

This emotional reactivity is not someone’s personality but a direct consequence of the body’s physiological stress response. When imposter syndrome has been eliminated, the person becomes routinely calmer and this emotional reactivity disappears.

The company costs of imposter syndrome include lower performance (than full potential), decreased retention from burnout or execs simply quitting and the cultural impact of burnout and reactivity.

When there aren’t enough women at the top, women suffering from imposter syndrome don’t have role models to aspire to.

They don’t have someone there who can confide that they suffer from imposter syndrome too, and yet have made it anyway.

And that leader who suffers from imposter syndrome? Everyone else can see they are competent and high-achieving, no matter how the individual feels themselves.

The biggest thing that organisations can do to help is to get more women into the pipeline and keep getting them to the top.

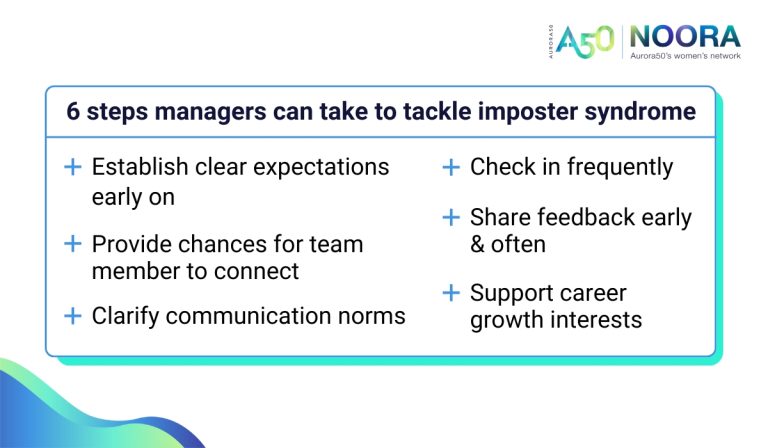

Another is to train managers about imposter syndrome, because it can create a negative, reactive company culture if you have fearful leaders afraid of being ‘found out’, and that can affect hiring and retention.

And everyone should be talking openly about feeling imposter syndrome, because most of us feel it sometimes.

As a manager, if you see someone not contributing when you know they’re a subject matter expert, draw them into the discussion and then talk to them one-to-one later on about their effectiveness and contribution to the team.

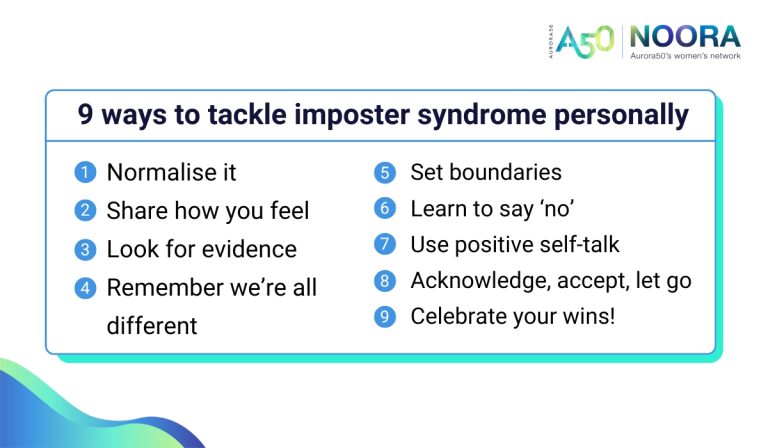

Remember your successes and why you really are qualified to do the job you do.

Acknowledge your imposter syndrome but don’t let it hold you back – feel the fear and do it anyway! Keep saying yes to opportunities.

Talk it out with managers, mentors, family, friends so you can work out where your imposter syndrome is coming from and how to manage it.

It’s OK to have setbacks along the way: overcoming imposter syndrome is an ongoing process.

If you are a manager – read the steps above for how businesses can help.

And take heart – a recent study showed there are benefits to imposter syndrome. People who feel like imposters are actually more empathetic and better listeners.

Never feel alone again – join NOORA, the network for corporate GCC business women who lead with impact and share their successes to rise together. Organisations can buy corporate packages and individuals can self-fund their membership.

Since 2022, UAE private-sector companies have been pledging to put women in 30% of leadership roles. Find the full list of companies here.

Don’t start a sentence with ‘I’m sorry but’. Women get interrupted 50% of the time in meetings; here’s how to amplify your voice (and the voices of others).

Ahead of COP 28, we look at the UN’s 17 sustainable development goals, and how the UAE is aligned.